I love cricket. When I was younger I enjoyed playing for my local team, Basildon, captaining the junior age groups, even making an appearance for Essex U15s. Success continued in the mens teams with the odd mention in the local paper. But what, if anything, has cricket got to do with Scrum? During my time working with Scrum teams I have often use analogies and metaphors to help aid in understanding new concepts. As part of this I have been able to use my cricket knowledge and experience to help individuals, teams and organisations in understanding Scrum.

Isn’t Scrum a rugby thing?

The term Scrum was first used in ‘The New New Product Development Game’ (1986) drawing parallels with a scrum in rugby, where members of a rugby team work together to gain possession of the ball and move it downfield towards the teams ultimate goal – scoring a try. However, rugby is not the only sport where parallels and analogies can be drawn with the Scrum framework; others including ten pin bowling and cricket.

But before we get into the detail of the parallels are there between cricket and Scrum, there may be a few of you that are asking what cricket is. Here is a quick (and very simplified) overview for those of you who may be unfamiliar with the sport.

- Cricket is a bat and ball game played on a field between two teams, each consisting of eleven players

- At the centre of the field is a 22-yard long pitch, with a wicket at each end that consists of three stumps and two bails

- The teams take it in turn to bat and field

- A member of the fielding team will bowl the ball and try to get the batter out

- The batter will try to hit the ball and score as many runs as possible

- After the first team has batted, the second team will bat, trying to beat the total set by the first team

- The first team will try to bowl the second team out before they reach the total that they set

- There are several variations of cricket that see the length of the game range from 100 balls to 5-days, with each format having nuanced rules

Cricket, like Scrum, is iterative

Although there are various formats of cricket that can be played in just a few hours to 5-days, they each have an iterative approach that could be aligned to the time-boxes that we see within the Scrum framework. The following table suggests how the time-boxes seen in Scrum could align to periods of play in cricket.

| Scrum Time-box | Scrum Overview | Cricket Time-box | Cricketing Parallel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Scrum | At the Daily Scrum the Scrum Team have the ability to inspect their progress toward the Sprint Goal and adapt their plan for the day ahead | Single Delivery | Before each ball is bowled the fielding team have the opportunity to respond to the previous ball bowled and tweak their strategy. They can, for example, position fielders in the best place to take a wicket or to prevent the batting team scoring runs |

| Sprint | At the end of a Sprint a Scrum Team will review the completed work, generate new ideas for delivery, reprioritise the Product Backlog and pivot to ensure maximum value is delivered | Over | At the end of each over the fielding team have the chance to take stock of the state of the game and change direction through a change of bowler (and potentially bowling style) from the other end of the pitch |

| Release | Although a Product Increment may be potentially releasable at the end of a Sprint, it is often the case that the outcomes from several Sprints are combined to form a release | Session/ Innings | Depending upon the format of the game, teams will have milestones that they will want to reach after ‘x’ overs. The type and circumstance of the game will determine number of overs that contribute to a milestone and what that milestone may be |

Cricket, like Scrum, offers the opportunity to inspect and adapt

At each of the stages described above the fielding team have the ability to inspect the situation they are in and adapt appropriately. They will take into account the state of the game, the condition of the pitch and ball, the competency and flow of the opposition batters, and the ability and form of their own players in order to make decisions about their strategy for the next time-box.

For example, at the beginning of a test match innings when the ball is new, a faster bowler may be employed to swing or seam the ball with a view to getting the batter to edge the ball to the waiting slip fielders. With more fielders in the slips there will be less fielders in other areas, offering the batter to the opportunity to score runs if the ball is not delivered to the field that has been set. Alternatively, later in the game, having a field with a short-leg and multiple men on the leg-side boundary could suggest that the bowler will be pitching the ball shorter in order to entice the batter to hook the ball.

The batting team will need to respond to this changing environment and inspect and adapt their approach. Dependant upon the situation that they are in they may need to be defensive and play the ball on its merits, they could try to pre-empt the type of delivery based upon the field that has been set, or, adopt a change in mindset to be aggressive in order to score runs more quickly as wickets fall and the number of ‘recognised’ batters diminishes.

Cricket, like Scrum, requires a cross-functional team

Teams, be it a cricket team, or a Scrum Team, require individuals with different skillsets. The individuals on the team will each have a primary skill and will work together in order to achieve a team goal. Where an individual has more than one area of expertise, they could be considered to be ‘Pi’, ‘M’, or ‘comb-shaped’ individuals, all of which can provide different benefits to a team.

The above inspect and adapt examples have already illustrated various high-level cricket skills, such as batting, bowling and fielding, which could be akin to some of the high-level skills of a Scrum Team, e.g. design, development, testing etc. This can be taken a step-further when comparing a fast bowler and a spinner to developers who develop using different coding languages.

Although cricketers will have that primary skill for which they will be selected, they could all be considered T-shaped individuals. This is due to the fact that as well as undertaking that primary skill, i.e. batting or bowling, they will also field. Depending upon their proficiency as a fielder, they could be seen as a ‘pi-shaped’ individuals. An example of a ‘pi-shaped’ cricketer is the England one-day international and Twenty20 captain Jos Buttler, who is a wicket keeper batsman in all three formats of the game.

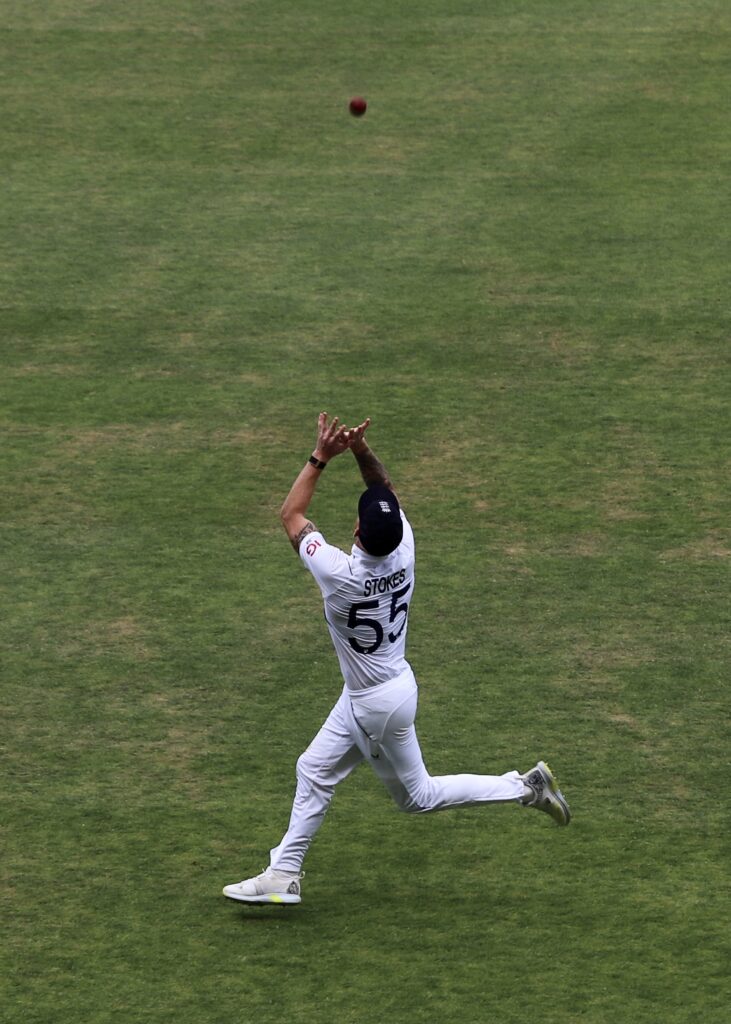

There are also cricketers that could be seen as ‘comb-shaped’ individuals. The current England test match captain Ben Stokes is one such player. Stokes made his test debut in the 2013-14 Ashes series in Australia showing his potential as a batsman in the second test, where he scored a hundred, and as a bowler in the fifth test where he took 6-99. But there is more. In the 2015 Ashes test at Trent Bridge he took a stunning catch off the bowling of Stuart Broad. He followed this with another ‘worldie’ in the opening game of the 2019 Cricket World Cup against South Africa. His batting in the final of that tournament helped England to win the trophy for the first time, and who can forget the heroics of Headingley against Australia in August 2019 (just six weeks after the World Cup Final win). Now Stokes is England test match captain and a true ‘comb’. Players such as ben Stokes are often the difference between a good team and a great team, commanding the highest salaries in the franchised formats of the game.

Cricket, like Scrum, can generate insightful metrics

Many Scrum Teams will have a set of standard metrics that are regularly produced and used as part of their delivery lifecycle in order to understand more about the progress of the current Sprint, the impact of improvement initiatives, delivery forecasts etc. Cricket is no different. Each time a new batter comes to the crease, a bowler starts a new spell, either reaches a milestone, or an innings/session comes to an end, a set of statistics are shared on our TV screens. The totals, averages and previous accomplishments are there to act as a guide and set expectations of what is to come.

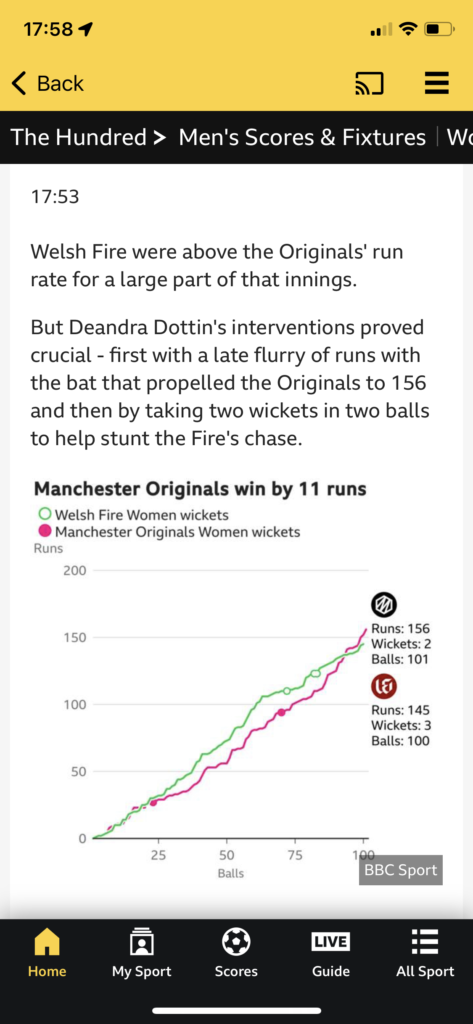

As play continues, additional information may be shown about individual form during the current series or calendar year, which could be a better indicator of what may be coming compared to a career average. Information about team performance is shared through the scorecard, run rates and over rates. These become more prevalent in the shorter formats of the game where time is increasingly limited. Here you are very likely to be show a histogram of the number of runs scored in each over, or an overall score comparison line graph. These types of graph are very similar in their composition to a velocity chart or burn-up chart.

The line graph (above) shows the scoring rates of the two team, allowing for a comparison as to whether the second team is ‘on track’ to achieve the required target within the time-box, just as a burn-up chart will compare if you are on track to deliver all the work within a Sprint/release. In this example, the Welsh Fire were ahead of the Manchester Originals scoring rate for the majority of the their innings, but a few late wickets slowed the rate and they ultimately failed to achieve their goal and lost the match.

Cricket, like Scrum, will use empirical evidence

All of this data may begin to impact how players approach the next ball they will face or the next delivery that we will be bowled. As a batter do I need to be aggressive and pre-meditate how I will play the next delivery, or, do I need to be more circumspect and ‘play time’ as the bowlers are on top? Conversely, a bowler will arrange their field according the the delivery he will be attempting so as to attempt to take a wicket or prevent runs. Does this also give insight to the batter as to the type of delivery to expect? This could be seen as the beginning empirical evidence.

The best examples of empirical evidence within cricket are when a new batter come to the crease and the captain and bowler make an immediate fielding change. This change suggests that they have a plan as to how to get the batter out, which will be based upon recent dismissals. In the test series against New Zealand in 2022, England had a plan for the New Zealand test captain, Kane Williamson, putting in a leg-slip. This tactic almost worked as shown in this video clip of the highlights from day one of the third test.

Nathan Leamon is England’s lead analyst. In 2021 he released a book with Ben Jones called ‘Hitting Against the Spin’, in which they explore crickets hidden working and dynamics through the analysis of the multitude of data that is collected. In an interview with Michael Atherton shown on Sky Sports, Nathan talked about the role of data analysis in cricket. He talks about the data driven analysis and empirical evidence to provide a clearer view and things that may not be seen with the unaided eye.

In particular Nathan discusses discusses the decision at the toss where a captain will decide whether to bat or bowl. The analysis shows that before 1970 36% of test matches were won by the team batting first. This is likely to be as a result of uncovered pitches, with the best time to bat being at the beginning of the game. This shifted between 1980 and 2010, where 36% of matches are won by the team batting second, with 31% won by the team batting first. However, it was noted that around 70% of captains still batted first when they won the toss, because of that ‘received wisdom’.

In the interview Nathan states:-

“The beauty of stats is that they never tell you anything about one instance. They can show you patterns, they can show you trends, and they can hopefully lead you to a better understanding of what is going on, but on any given day it might be the right thing to bowl first.”

Nathan Leamon – Sky Sports

Cricket, like Scrum, embodies a number of values

The earliest references to cricket are from the mid-16th century, with the sport spreading globally during the expansion of the British Empire. The Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) was founded in 1787 and the following year they laid down a ‘Code of Laws’, which were adopted through the game and to this day the MCC remain the custodian and arbiter of Laws relating to cricket around the world.

During the late 1990’s two former England cricket captains, Ted Dexter and Lord (Colin) Cowdrey, sought to enshrine the ‘Spirit of Cricket’ in the game’s laws. This initiative proved successful in 2000 when the update Code of Laws included a ‘Preamble to the Laws: Spirit of Cricket’. This was added in order to reminded to players of their responsibility for ensuring that cricket is always played in a truly sportsmanlike manner.

“Cricket is a game that owes much of its unique appeal to the fact that is should be played not only within its Laws but also within the Spirit of the Game. Any action which is see to abuse this Spirit causes injury to the game itself.”

Preamble to the Law: Spirit of Cricket – www.lords.org

In 2016 the Scrum Guide saw the addition of Scrum Values; commitment, focus, openness, respect and courage. Although the Scrum Values were not detailed within the initial versions of the Scrum Guide, their subsequent inclusion has helped to provide additional direction of the behaviours and actions expected of Scrum Teams.

The addition of the ‘Spirit of Cricket’ and Scrum Values do not detract from or change how runs are scored, wickets are taken, the roles of individuals in cricket/Scrum, the Scrum Event or Scrum Artefacts. What they have done is to help influence, for the better, how ‘the game’ is played, guiding players as to how to behave rather than looking to detail each potential scenario.

Cricket is like Scrum

So, cricket is like Scrum. There are a number of parallels that can be drawn between the two that can assist in describing and understanding Scrum.

If you liked reading about the parallels between cricket and Scrum, you may also like to read my blog post on the Agile Mastery Institute website that asks ‘can the 7 principles of ‘Bazball’ be applied to Scrum?’.